Not to get too gross or salty about it, but I’d say, given “Kings of the Road,” I don’t think Wenders owes us anything in the shit department. (In this late ‘70s film the lead character relieves himself on a beach on screen; the action is depicted naturalistically and nonchalantly, in long shot; nevertheless, one commenter on Roger’s review pronounced the scene as “sick.” Damned if you do, damned if you don’t, I guess.)

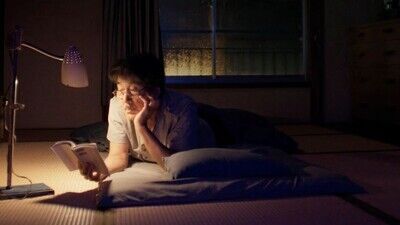

But beyond what he does not show, there are a few critics I’ve seen who can’t abide the concomitant attitude of Hirayama and the movie itself. Which I took to be “acceptance is the key.” For some the distinction between acceptance and complacency is non-existent, and I get that. Nevertheless, I was consistently moved by this picture and by the serenity sought and often found by its protagonist.

In any event, the movie has its mysteries, and these mysteries look to another side of life, one not so serene. The patience and tolerance that Hirayama shows his chowderhead colleague Takashi (Tokio Emoto) is extreme enough to border on self-abnegation. When Hirayama’s teenage niece shows up at his door, we get a hint of familial unease. The girl is mildly curious about her uncle’s way of life, and borrows one of his book, a collection of Patricia Highsmith short stories. A little later, the girl, Niko, tells Hirayama that she particularly admired the story “The Terrapin.” The movie itself doesn’t divulge this, but that story is about a kid whose mother boils a turtle (which indeed had been brought home to be eaten); the kid retaliates by stabbing his mother to death. When Hirayama’s sister shows up to claim her daughter, the dialogue between siblings alludes to a former mode of life very different from Hirayama’s current situation. Is Hirayama doing a living amends? And if so, for what? “I like to think you killed a man, it’s the romantic in me,” Captain Renault says to Rick Blaine in “Casablanca,” speculating as to what Rick has been running away from. One again thinks of the Highsmith-based “The American Friend,” and the anti-romantic killing in that film, and wonders what Hirayama might be running from.

The movie reminded me of what Peter Bogdanovich said of Ford’s “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”: that it “is not a young man’s movie; it has the wisdom and poetic perceptions of an artist knowingly nearing the end of his life and career.” The wisdom and poetry here are just as real and just as thoroughly felt.