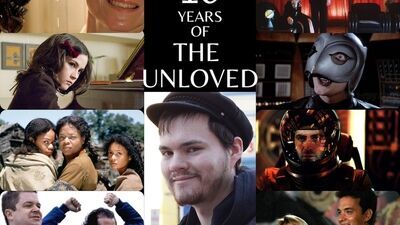

The Unloved series has always been a pivotal part of RogerEbert.com, and not just for how it gives Scout’s taste the platform it deserves. But because in the middle of watching a video essay about a critical assessment you may or may not share in your guts, a sentiment is clear: Watch more movies. There’s always going to be more to love, and more to talk about. – Nick Allen

One of the first installments of Scout’s “The Unloved” series I can recall obsessing over was his video essay on Michael Mann’s “Public Enemies,” which emphasized the extent to which Mann’s experimentation with digital cinematography transformed his approach to period filmmaking and elevated his story of brutal gangsters and dogged lawmen into a vivid, unsettling reflection on our relationship to history and its narratives of violence, self, and celebrity. Throughout this essay, published ahead of Mann’s “Blackhat” hitting theaters, Tafoya discusses the initial reception to “Public Enemies,” his own reappraisal of Mann and cinematographer Dante Spinotti’s use of digital cameras, and the impact of this stylistic choice on the film’s interrogation of image-making—individual and collective, cultural and romantic—throughout American history. As Tafoya illuminates, a fascinating effect of “Public Enemies” looking and feeling the way it does is a certain construction of reality, the sense that audience members could at any point reach through the screen and grasp the past, coming face-to-face with those mythic figures that loom impossibly large in our popular imagination. “In quieter moments, Mann and Spinotti zero in on Johnny Depp’s pores, which means looking directly into the scarred face of infamy: movie stardom,” Tafoya notes. “It turns legend into fact. But the mere fact of seeing the very real and very human face of Depp turns an actor into a person—and his elemental performance, million-dollar smile, and feline eyes back into a legend.” Tafoya’s video essay on “Public Enemies” is also an archetypally polished entry in “The Unloved” series: precise, perceptive, and made with a combination of visual flair and poetic commentary. “Life and death have never looked so real and unreal at once,” Tafoya offers as a parting line. “This is how we lived. This is how we died. It has always been so.” – Isaac Feldberg

Scout’s essays are a treat when he validates my affection for an under-appreciated film, and he somehow nearly always surprises me by focusing on elements I overlooked. But I enjoy even more his essays for films I do not like. I can’t say he has ever persuaded me to change my mind, but I love the way he sees them and his willingness to speak out on their behalf. – Nell Minow

I never thought that, ten whole years ago, I’d watch a video essay about a maligned David Fincher movie and gain not just a colleague, but a dear, dear friend.

And yet, that’s what happened in my cramped garden apartment in Chicago, huddled over my laptop, staring with rapt fascination at a new video essay I’d stumbled across on RogerEbert.com. The film in question was David Fincher’s “Alien 3,” a film I genuinely believed that only I loved—a blockbuster franchise turned into a melancholic, industrial tone poem, one which threw caution to the wind and disrupted the feel-good ending of the franchise’s prior entry by killing off the found family that survived it. In so doing, it became a fascinating portrait of its own failure, where Ripley, like her then-freshman director, stalwartly resigned themselves to the grim, beautiful fate destiny had carved for them. And here was a young man, a gifted writer around my age with twice my talent, articulating those feelings of messy rapture through a signature, aching rasp, one weary but tinged with wonder.