“The Book of Clarence” is a religious epic that isn’t particularly religious: Despite Clarence’s twin brother Thomas (also played by Stanfield) being one of Jesus’ apostles, Clarence is a cynical atheist. He is also a drug dealer, selling and smoking a copious amount of weed. Club dens with nearly nude, sensually gyrating women and shady characters fill his world.

Clarence also isn’t the brightest light in Jerusalem. Take the film’s opening scene: To make some extra cash, Clarence borrows money from a notorious gangster named Jedediah the Terrible (Eric Kofi-Abrefa) for a chariot race against Mary Magdalene (Teyana Taylor). It’s not quite clear why Clarence thinks this a safe bet or even a lucrative opportunity, especially considering the risk involved. Still, Clarence and Mary’s contest, shot on location (Matera, Italy is the real-world stand-in for Jerusalem), is surprisingly immersive and refreshingly practical. In a scene dearly indebted to “Ben Hur,” their chariots, pulled by real horses, thunder down old-world streets with precision. Rob Hardy’s cinematography is so tangible in this sequence, aided by point of view shots from within the carriage, you can feel the wheels rumbling underneath.

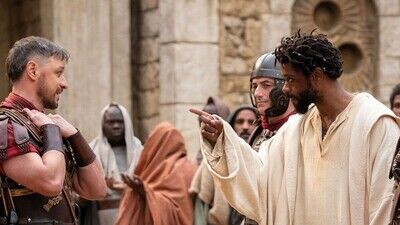

Clarence and his best friend Elijah (RJ Cyler), of course, lose terribly to Mary. Their defeat means they need to find a way to scrape together enough cash to pay back Jedediah. At first, Clarence considers being baptized, believing God will protect him. It’s an idea so vain that John the Baptist (an inspired David Oyelowo) hilariously slaps him. Then Clarence decides to become an apostle, believing that Jesus’ gang of made-men, so to speak, will protect him. Even that strategy has a few problems: Clarence, as you recall, is an atheist; he is also estranged from his brother Thomas, who not only abandoned their mother (Alfre Woodard) but is also embarrassed by Clarence’s presence; also, when given the chance, Clarence fails at the task provided by the other disciples when he only manages to free one gladiatorial slave, Barabbas (a captivating Omar Sy).

These failed hustles are laboriously paced by the film’s misplaced humor, which only becomes creakier when Clarence decides to get-rich-quick by posing as a new messiah. This lightbulb moment—seriously, an actual lightbulb appears over Clarence’s head—happens nearly halfway through the film. From that point on, you wonder exactly who is the audience for this movie. See, Clarence doesn’t believe in the immaculate conception or that Jesus performs actual miracles. He thinks Jesus has become famous by crafting elaborate tricks. The film therefore tries to walk the very thin line between lampooning Christianity and setting Clarence on a journey of self-discovery. The more it attempts one, the greater the other suffers—leading to excruciating jokes that rarely, if ever, rise above a slight chuckle.