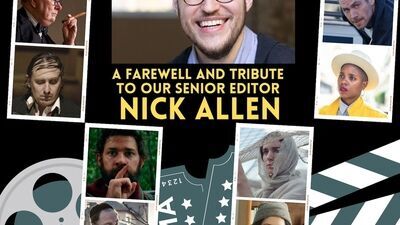

In addition to overseeing and editing the work of others, for the past eight years, RogerEbert.com Senior Editor Nick Allen has been one of our site’s most prolific and invaluable writers. He began by writing dispatches at the Sundance Film Festival in 2015 before going on to cover other major festivals such as SXSW, Telluride, Toronto, Fantasia and many others. The interviews, essays and reviews—both for film and television—he penned for us are a treasure trove that can be found in their entirety on his Contributors page, but with Allen leaving his position at the site this week for an exciting new job, we are spotlighting fifty-one of his articles in this special tribute. We hope you enjoy them.

In his Meet the Writers interview, Allen shared a moviegoing experience that he will never forget: “A public pre-release screening of ‘Fast & Furious 6,’ for the way that an audience reacted when the sound didn’t work for the first 10 minutes. Everyone started making cartoonish car sounds during an opening chase scene for a bizarre yet touching communal experience. The movie itself was a particularly good time for me as well.” The “Fast & Furious” franchise become one of many cinematic works lucky enough to be examined and championed by Nick.

The excerpts that follow are split into four categories: film reviews, interviews, TV reviews and essays. Click on each article title, and you will be directed to the full piece.

On a personal level, Nick is kind and compassionate and we hope you join us in wishing him well in his new endeavor. He will be missed.

I. FILM REVIEWS

Boulevard

With dramatic scripts, Williams was a hushed force that offered something painfully human, and a talent who would go to the darkest depths with directors who had the right story (ex. Bobcat Goldthwait’s “World's Greatest Dad,” the definitive Williams role in the 2000s). The ingredient he brings most to “Boulevard” is heartfelt empathy, which makes this portrayal heroic.

Stinking Heaven

Nathan Silver’s “Stinking Heaven” achieves greatness on its own terms. It’s a film to sift through, lacking usual narrative comforts like easily understanding who’s who, a stable visual sense of their physical space, or even a chance to breathe, as these lives feel to have been well in motion long before we are placed in the room. And yet, “Stinking Heaven” is an incredibly refined emotional experience, the splattered emotions on its dirty canvas nonetheless the product of a specific, deeply felt directorial vision.

Pervert Park

“Pervert Park” is an extraordinary film in part for how it challenges a documentarian’s decision to put a camera on a crying face like Tracy’s, and to hold on it as a type of emotional climax. There’s not an inkling of a dramatic jackpot within these powerful moments, captured with the same lack of intrusiveness as when cameras simply follow residents around in B-roll footage. These shattering scenes instead are breakthroughs between the subjects and the audience, incredibly tough minutes that complete the goal of humanization.

Blood on the Mountain

“Blood on the Mountain” is wide-ranging across time, driven by talking heads and select footage, but it nails the human element at its core. It savors the visual poetry to be found in place where a person’s existence depends on their bodies instead of their minds, offering numerous somber shots of small towns dwarfed by coal rigs, or mountains of coal overlooking homes.

One Week and a Day

“One Week and a Day” is an incredibly tactful tragicomedy from debut writer/director Asaph Polonsky about two parents figuring out what to do next after their son dies. In the long list of movies about death, this is one of the most original in recent memory, if for its emotional delicacy in sparing us hollow, tear-gushing grandiosity, and for its attitude on life: In most movies about grief, you are waiting for the characters to cry. This is a marvelous story about loss in which you are waiting for them to laugh.

Menashe

Like all great films that nudge the world toward being a slightly more compassionate place, the creation of “Menashe” is an act of empathy. Co-writer/director Joshua Z. Weinstein’s film achieves this initially by putting a soulful gaze on a world we rarely see in American film, the Hasidic community of New York City, using non-actors who speak entirely in Yiddish. But the emotional focus is what makes the film so incredibly special. Here is a film dedicated to recognizing our most common obstacles, its quiet storytelling largely accompanied by those feelings at the bottom of anyone’s gut: guilt, shame, defeat. “Menashe” is a gorgeous ode to everyone’s inner screw-up.

For Ahkeem

As “For Ahkeem” so deeply puts into the feelings of Daje and Antonio, the influence of older authority figures is highlighted. The dichotomy is heartbreaking and revealing—members of the older generation who come from the same place, and are at the school or in the neighborhood, reach out to them as fellow human beings. “Trust and believe, we gonna make it,” a woman who serves lunch tells Daje, before telling her to walk like a queen.

Pass Over

Using numerous camera angles and expressive editing, Lee’s filmmaking emphasizes the emotion on Nwandu’s pages, like the abrupt cuts to Moses and Kitch dropping to the ground whenever they hear bullets. Extreme close-ups are utilized in very select passages, mirroring the immediate fourth-wall breaking monologues and word-less gazes of various projects of Lee’s past. There are sequences in which “Pass Over” uses so many cuts and different angles that it plays like a film that was shot on a very minimal set, as if unfolding in some type of microcosm—a further testament to the project’s artistic grandiosity.

Makala

This existential tale is truly captivating, like the feeling of getting sucked into Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich as it shares every banal detail of poor Ivan’s life. The potency for stories like these comes from making us process what’s under the microscope; suddenly, the smallest of occurrences are magnified in their importance, and a bare bones objective naturally achieves high stakes.

Mary Magdalene

For centuries, the Greatest Story Ever Told had it wrong. Mary Magdalene, one of the most recognizable women in the Gospels, was not a prostitute, but an Apostle just like Peter, Matthew, or Judas. It was Pope Gregory back in 591 who started this misrepresentation, which wasn’t fully addressed by the Vatican until 2016, when they restored Mary back to her place as one of the most important people in Jesus’ circle. That is an extraordinary correction—whether one considers the narrative to be history or just a story—and it is propagated here by an extraordinary film.

Cunningham

There’s been nothing quite like Alla Kovgan’s “Cunningham,” an exhilarating testament to documentaries as a boundless form of art. A celebration of New York choreographer Merce Cunningham, the film dreams beyond restrictions many visual storytellers seemingly adhere to. As its narrative tells brief bits about Cunningham’s life, and puts his other-worldly dance routines center stage while accompanied by flourishes from 20th century avant-garde music, “Cunningham” honors the tools of filmmaking—sound, action, dialogue—with the harmonious blending of three art forms: music, dance, poetry.

Tiger King

The aesthetics of this story alone—Americana, tiger memorabilia, guns, bizarre facial hair—are a gold mine for a true-crime story, and many other stories would stay at the surface. But “Tiger King” digs deeper, seeking to explore what kind of person would own big cats, or give their life to someone who does. With nary a weak episode, “Tiger King” establishes rich dynamics of possessiveness, of individual kingdoms that can be destroyed from the inside just as much as the outside. This makes everyone’s many back-stabbings all the more vivid, especially as Joe later on has to fight for ownership of his zoo, while balancing his political aspirations.

Driveways

“Driveways” does not comprise itself of many heavy dramatic beats, and yet it can still grab you with moments of empathy that alone warrant this movie’s existence. The best might be the one that gets the “plot” in motion—Kathy asides to Del while driving him to the VFW about the lack of electricity in April’s house, and how expensive it will be to get it turned on for just a few days. The next day, Cody and Kathy return to the house and see a stack of power strips, with an extension cord running from Del’s home. At a time when apathy has become disturbingly claustrophobic, such displays of surprising, quiet kindness are a true balm.

Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen

A project like this comes full circle with the clear passion behind it, especially as it tries to reach to viewers by sticking to a talking head documentary approach. Feder makes some vital choices, one of them being that every person interviewed is transgender. When a particular show is brought up for a discussion of its portrayal, the discussion is more about the experience of watching—which can be heartwarming like when actress Laverne Cox talks about discovering “Yentl,” or heartbreaking when actress Rain Valdez talks of watching “Soap Dish” with her family.

The Climb

It’s a jaw-dropping achievement as a directorial debut, but within the scope of all the funny movies before it that have relied on a bland point-and-shoot mentality—regardless of budget size—Covino’s film is an exhilarating anomaly, if not a wake-up call for the visual potential of heartfelt comedy. You can trace the script’s characters and situations back to shaggy Sundance-promoted indies, or glossy studio comedies, and yet “The Climb” has Covino making his own mark with cinematic ambitions that promise a career worth keeping a close eye on.

Allen v. Farrow

Everyone in “Allen v. Farrow” emerges more human than we’ve ever known them before, whether they’ve spent a life on-camera or not. Among its many successes, it prevails at getting you to see this no longer as a Hollywood scandal buried by a celebrated filmography but as the wrenching tale of an American family traumatized by a father’s choices and held together by unfathomable courage; a saga of revealing actions that are deeply horrific or heroic, always based in how one person chooses to treat another. Despite what some future headlines about this docuseries might say, there is nothing particularly explosive about “Allen v. Farrow,” so much as profoundly humanizing.

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings

“Shang-Chi”‘s thrilling’s embrace of clarity, of nudging your imagination instead of doing all the work for you, spreads the inspired special effects that enhance the magic of this story and the world of its characters. There’s an evocative use of water—it bursts from walls, floats in the air, and makes a map of icicles—a striking way of depicting a moment that usually would just get a hologram. The movie even throws in a charming animated cute sidekick that cleverly subverts the expectations of cute faces on plush-looking sidekicks.

I Love My Dad

James Morosini’s “I Love My Dad” grabs the eternal adage of “write what you know” and sprints towards the edge of a cliff. The story is true: Morosini’s father pretended to be someone else online in order to check in and be close to the son who had blocked him on social media. It’s such a bizarre concept, such a painfully sad move to be close to someone, that you have to laugh. “I Love My Dad” lets the viewer do that over and over, creating a roller coaster ride of one desperate and awful idea after another, one that’s bound to crash and burn albeit with confident style.

Fleishman is in Trouble

Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s “Fleishman is in Trouble” is a potent collection of crises, a mini-epic about being in one’s forties and not having everything figured out, as one might believe it all should be. That realization scares them. It makes them angry; it makes them run away. One’s marital status (happily together or blissfully apart) and having children doesn’t bind characters like Toby, Rachel, and Libby to a greater sense of certainty of themselves, which they only have a lens-flare-heavy sense of the past of which to fact-check. “Fleishman is in Trouble” is a saga across time, relationships, and even bounds of empathy that offers the best kind of whiplash. When this FX adaptation’s excellent cast and storytelling are truly in sync, its wisdom can be inescapable.

Beau Is Afraid

No rule says one needs a certain amount of features before reckoning with their authorship. “Beau Is Afraid” is, appropriately, like a fever dream through the museum of Aster’s previous creations and fascinations—it’s not just the 2011 original short film “Beau,” but the premise of his short “Munchausen,” the hellish city landscape of “C’est la Vie” (starring Bradley Fisher, the man playing the role here of “Birthday Boy Stab Man”) and Aster’s fixation with head trauma, communes, etc. Part of the movie becomes like a retread of what built “Hereditary,” which is rendered all the more intensely personal by this film’s jarring use of first-person point-of-view shots (a terrified boy nodding to his mother) and its bookending scenes. The first scene of “Beau Is Afraid” is what this movie’s personal nature looks like on the outside. The final scene shows us what it feels like for it all to be entertainment.

The Year Between

Writer/director Alex Heller pulls off a dazzling tonal high-wire act for her directorial debut, the story of a bipolar 20-year-old woman named Clemence. In the first act of “The Year Between,” she moves back in with her family to their small Illinois town, is diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and is set on a foggy path of learning what medications and life choices will give her a balance. Clemence is in nearly every scene, sharing the movie’s humble Midwestern backdrop with different family members, possible new friends, and high school throwbacks. The uncertainty in these interactions provides the movie with its main stakes, and when Heller’s writing is so rich as it often is, that’s all the viewer needs. Best of all, the film’s dialogue is naturally, wildly funny, without sugar-coating the issues it embraces.

II. INTERVIEWS

Keanu Reeves on “Knock Knock”

I don’t really play with my image. But I was sent the script by [producer] Cassian Elwes, and I responded to the material; the idea of playing this guy who goes through this journey, who is really guilty and innocent, but mostly guilty, and gets punished. And, in a way, he kind of grows up. But that’s just one aspect of it. I enjoyed the script because it was funny, and I liked the suspense that Eli was playing with. I’ve always wanted to work in a different genre, and I love when films can entertain but have ideas in them.

Sir Ben Kingsley on “Learning to Drive”

Since I’ve done fifteen years in the theater as you know, and since moving from the theater to movies, I think of myself more as a portrait artist, rather than a landscape painting. Theater is landscape painting, and cinema is the delicate process of getting one individual’s face onto the canvas, or the screen. So, I try to present a portrait of a decent man. And a man who is committed to doing the right thing.

Sarah Silverman on “I Smile Back”

I’m from a stand-up comedy background, where everyone is kind of responsible for their own thing, it’s not a team sport like acting. And it is acting, stand-up. I defend that. My heart gets broken when I think about that Joan Rivers’ greatest sadness was that she wasn’t seen as an actress, because it is acting, you’re honing this act that you’re doing for a year, two years, and making it seem like you’re saying it in the moment.

Gregg Turkington on “Entertainment”

When I have the audience won over, I like to start throwing some jokes that aren’t as friendly, or that are duds. And then when I start to feel like I’m starting to lose them, then I come back with things that I know will win them back. It’s a little bit of a kind of game, but I like that roller coaster ride. I feel like it makes for more of a memorable evening.

Todd Haynes on “Carol”

My very first movie, “Mary Poppins,” which I talk about, it just turned me into an obsessive, creative creature who had to sort of reply to the experience by drawing things, making things. It was like it forced, it made me into this obsessive, creative creature … I don’t know any other way of putting it. And in some deeply primal way—I’m sure there’s something about that maternal figure and maybe there’s all these kinds of Freudian roots to that, that I’ll lead to somebody else to extrapolate like you—but I think it was the power of the experience of watching a movie that just riveted me.

Mike Birbiglia on “Don't Think Twice”

I wrote this thing on my wall when I was writing the film, I wrote, “art is socialism but life is capitalism.” That was this guiding principle that I had which is like, no one ever says it because it’s too on the nose, but I thought an interesting idea for a movie. This idea that, when we gather together, we can embrace socialist ideas, like we’re all equal, we’re all in it as a group, and we’re all in it together and going to help each other. And then when push comes to shove, people really look out for themselves.

John Legend on “Southside With You”

I wanted to write something that was intimate, because the whole film is very intimate to me. Even though they’ve lived these big lives, this date, and the film, are both very simple and intimate. I wanted the song to feel like that too. And the lyric, of course, kind of talks about the idea of the start of a relationship, and the uncertainty that you might feel something new with somebody and you don’t know where it’s going to go, but you know it won’t go anywhere unless you start.

Tyler Perry on “Tyler Perry’s Boo! A Madea Halloween”

Having my son be born during that time, it was all about him, and I had to stop and gather myself and my thoughts and figure out how to adjust inside of fatherhood with all of this. He was the purpose for the break, until I could get my arms around that. But definitely what happened was, “Gone Girl” changed everything for me. And I learned so much on “Gone Girl” that the next film I do—you won’t see this in “Madea,” I mean, Madea is Madea—but the next drama that I do I think you’ll see a lot of what I learned on those sets.

Michael Shannon on “Nocturnal Animals”

This Trump thing is like getting a box of firecrackers, or something. It’s like, ‘Well, this will be fun for a little while, this’ll kill some time.’ Because, y’know, the jackass will be amusing on television, say stupid shit. Make everybody clap. Hillary would have been too boring, I suppose. It’s the worst thing that’s ever happened. It’s the worst. This guy is going to destroy civilization as we know it, and the Earth, and all because of these people who don’t have any idea why they’re alive.

Janicza Bravo on “Lemon”

People refer to characters like this as unlikable, which I don’t think about or process him in that way. But I think in dramas, for whatever reason there’s more permission for characters who are like [Isaac], who are deeply flawed but we’re still sort of rooting for. And in comedy, I think the audience is signing up for a certain type of pleasure. And so if you’re not delivering on that pleasure, then you haven’t shown up for your end of the bargain, right?

Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis on “Whose Streets?”

[Davis:] I’m concerned with speaking to the choir, and trying to get them, because those are the people who show up to church every Sunday, those are the people that need saving. And I think we spend too much time trying to breathe empathy into people. I think the people that see it, if they can see humanity in people, they’re going to see it. And if they don’t, then I’m not finna lose no sleep over those folks.

Gary Oldman on “Darkest Hour”

People roll their eyes when I say it’s three-and-a-half hours in makeup, and they ask, “Did you go crazy?” It’s knowing about what you’re getting into. We had tests, I wore the makeup, with the tests that we did I wore the makeup 63 times. And I wore it 48 consecutive days in the shoot. You know what you’re getting into. You have to surrender to it and enjoy it as enjoy it as part of the character and the whole process of this. Otherwise, I know actors who are kicking and screaming and going crazy, and they can’t bear the claustrophobia. But it’s oddly very freeing.

Steve Carell on “Vice”

There isn’t one type of thing that I feel comfortable playing. I actually think that’s sort of a trap, to think there’s an easier, or more comfortable, easy thing to play. Generally, I don’t play things that I think I feel comfortable playing, because that’s not so much … I feel like it’s good to be a little bit afraid of playing something. I think a little bit of trepidation can get your juices flowing [laughs] and helps you out in the long run. I really do. If you become complacent, if you think you know what you’re doing, odds are you probably aren’t doing what you should be doing.

Bennie and Josh Safdie on “Uncut Gems”

[Josh:] Someone who can’t get out of their own way is something that, in a weird way, we can relate to. We couldn’t get out of our own way, this was the movie that we had to make for so long. And you have these principles that you just kind of stand by. It’s like … everyone once in a while, someone will send us a script or their agents will, and we’ll read it. And you hear, “This is the script that everyone wants,” and you read it, and you’re like, “This is the script that Hollywood thinks is going to be a huge hit?” The exposition is so naked, all these things. But we could do that. In a weird way. We could. But at the same point it’s like, but I can’t do it.

Judd Apatow on “The King of Staten Island”

I think the whole world is trying to figure out their spirituality. I am obsessed with self-help. At any given moment I might be reading Courage to be Disliked, or Rest: Why You get More Done When You Work Less. I know it’s funny that everybody is on their calm app, or reading their Eckhart Tolle book, I know I am. We’re all lost and trying to come up with some lifeline that helps us through the day. It’s especially funny when that’s happening on Staten Island.

Miranda July on “Kajillionaire”

I always hope that this filmmaking medium that started out so completely out of reach … like the least successful medium you could ever dream up … that it’s going to be radically changed by all the people who are now able to tell different kinds of stories. And that eventually we’ll look back on the beginnings of the medium as just the early history of it, and that it started out as this kind of very narrow elite tool, and became something like the written word.

Aubrey Plaza on “Black Bear”

I love being directed. I’m definitely not one of those actors that wants to be left alone, and not directed. It’s such a collaboration for me, and I want to be directed in creative ways. I don’t want to be told to give any end result, I want to be asked questions, I want to be inspired by my director. And I want to feel safe, I want to feel like they really got me. Then I can really be vulnerable and expose myself.

Alicia Vikander on “Blue Bayou”

A good director will say, “Ah, Alicia tried something new there,” and when I do it, I feel, “Something happened there. I should have followed that instinct more.” And a good director, I feel, sees that. And you just look at each other, and they look at you and you understand that they saw you were doing something, and they’ll say, “Do it again.” That is magic to me, someone who has that emotional intelligence, and has that eye, and is able to communicate or make a space where the actors get to explore and stretch whatever they have, to dare and accomplish something and not to feel scared.

Sean Baker on “Red Rocket”

I’m here in the city, I’m part of the DGA, I go to events, if I get invited to a party, I go a party. But I feel very much of an outsider. And now I’ve reached the point where I’m not very interested in being accepted any more. I’ve found my own route, and the agencies only started paying attention to me, after “Tangerine” … no, it took Willem Dafoe being nominated (for “The Florida Project”) where they would email me and say, “You want to meet up with one of our clients?” Kind of too late guys!

Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert on “Everything Everywhere All At Once”

[Kwan:] It wasn’t that we wanted to be entertainers, we wanted to prove that the profound and the profane belong to each other. As above, so below. That’s what “Swiss Army Man” was trying to do, and we got a decent amount of people in, which is such a success in our books. We got some people to say, “This is our favorite movie ever,” what a miracle because it’s a farting corpse drama, you know? But for the haters, who just didn’t get it, who full-on rejected it, I felt like we failed them. I was like, “I’m so sorry we didn’t show you the truth.” The dung beetles, they’re rolling in their shit, but they also look to the stars to guide them.

III. TV REVIEWS

Amazon’s “Fleabag” is Dark Comedy Bliss

Aside from empathizing with a person who lies, cheats, steals and even calls herself a “bad feminist,” Amazon’s extremely binge-able “Fleabag” requires two things of its viewer. One, to not mind that its title lead character breaks the fourth wall often, as some might think that narrative trick is a turn-off. And two, to like Fleabag so much that we’ll follow actress Phoebe Waller-Bridge every step of this simultaneously raunchy and tragic life, as she is in every single scene, the whole six-part series about the current state of Fleabag’s shit life. But if you’re looking for some of the best entertainment you’ll see all year (on a screen, or perhaps even in life), “Fleabag” is dark comedy bliss.

HBO’s It’s a Sin is a Radiant Coming-of-Age Story in a Dark Period

“It’s a Sin” is essentially a radiant coming-of-age story balanced with the sense that the party could end sooner than later. It’s an often potent mix between that sense of feeling totally alive amongst your friends, especially at such an independent age, with the gravity of an epidemic that they don’t understand, that they aren’t informed about. Resilience becomes one of the story’s main spectacles, especially in how Richie, Roscoe, Jill, Colin, Ash and others seek to defy all of the various forces that threaten to muddle their deepest goals. But as each episode features a stunning character death, the shadows feel darker and the moments of light feel even brighter.

Disney+’s Loki is a Captivating, Christopher Nolan-Esque Chase Through Time

Before he gets on the mission, Mobius interviews Loki about who he really is, which involves showing Loki all of the betrayal and growth that happened in the later Marvel movies, but does not exist in this Loki’s current timeline. These scenes brilliantly function as therapy and character exposition, giving this villain the psychological reexamination that would only be interesting with so much backstory, and moments of this Loki emotionally seeing what he’s truly been capable of. This is all before the pursuit truly kicks off, but as an existential centerpiece of episode one, it’s captivating.

Hulu’s Only Murders in the Building is a Playful True-Crime Romp

The good news about Hulu’s “Only Murders in the Building” is that it’s just about as funny and charming as one would expect from a murder mystery involving Steve Martin, Martin Short, and an inspired addition to the duo’s renowned comic chemistry, Selena Gomez. And there’s little bad news, really, because the show has figured out its own brand of goofy and surprising, as it throws the three characters into a spiraling investigation without a great deal of danger. The suspicious death of someone in their building is a dream come true for them, and that’s a morbid, giddy joke in itself.

HBO’s The Staircase is a Masterful, Stark True Crime Epic

Firth takes his usually congenial, calm screen presence and shows us its flip side, that of being indignant, slippery, and clumsy, like if a Eugene Levy character in a Christopher Guest movie were accused of first-degree murder. But with the framing of the entire story introducing Michael to us in both the year of the murder, 2001 and as a free man in 2017, Firth withholds the conscience of his character, while showing the explosive emotional needs of his character. He’s incredibly hard to read, and just as fascinating to watch.

IV. ESSAYS

Unstoppable Force: A Look at the “Fast & Furious Franchise”

As cynicism about an adaptation-addicted Hollywood builds with the announcement of each new cinematic universe, or feature-length version of your favorite detergent, the “Fast & Furious” installments are outside of such anxiety, even when reaching a seventh chapter with this past weekend’s “Furious 7.” Underneath the series’ genre joy, and way beyond its initial impression as a series about street racing, the seven “Fast & Furious” movies are an example of the Hollywood blockbuster’s inventive potential. They are a movement of fruitful creative values that redefines the narrative limits of a poppy franchise, dares to vitalize a waning cinematic thrill, and honors a modern audience.

Entertaining the -Isms

Disregarding ideas like sexism & feminism in a film is a bastardization of the biological truth that human beings watch the same thing differently—a concept that makes movies worth watching, and talking about. (If we all started seeing the same movies in the exact same way, that would be a nightmare, and I would personally bomb the polar ice caps so that global warming could just finish us off already.)

Why John Krasinski Isn’t a Surprising Director for “A Quiet Place”

By no accident, he’s tackled the horror genre by relying on the unique strength that can be seen throughout his acting work, and one that has made him relatable as an everyman across TV and film—expressive silence. Years before Krasinski was silently reacting to the supersonic monsters of “A Quiet Place,” there was Michael Scott. The world met Krasinski on “The Office,” as one of many employees at Dunder Mifflin who, when rendered speechless often by Steve Carell’s insensitive, bombastic and in-turn-hilarious boss, shot glances of discomfort at the documentary crew filming them. But Krasinski’s work as paper salesman Jim Halpert elaborated beyond the original comic idea of glancing at the camera in pained recognition, and became an essential part of adding to the show’s deafening, deadpan awkwardness.

Hate Across America: On the True Nightmare Underneath Jordan Peele’s “Us”

There are many pop culture references in the movie, but the most important is front and center in the first shot. Surrounded by VHS copies of “C.H.U.D.” and “A Nightmare on Elm Street,” a TV plays an ad for Hands Across America. It speaks of the true event in 1986, in which millions of “Good Samaritans” would hold hands and “tether” themselves across the country, in an effort to fight homelessness and to show a sense of unity. The reference is an excellent deep cut from Peele, in part because Hands Across America failed, such an act then buried and forgotten within American pop culture.

Wes Anderson Evolves Signature Style in Four Netflix Short Films

These shorts are alive in a way that’s much like theater and rarely like modern movies, including Anderson’s previous ones. But instead of Anderson putting these stories on an actual stage, now they’re short films that provide the creative limits of theater with the forced perspective but the free rein of a camera. It’s an intimate production between Anderson and the viewer, performing these stories for you, putting on a show as if you were the additional character in these stories, but silent.

To find all of Nick Allen’s work published at RogerEbert.com, click here.