“The Seventh Victim” is almost certainly the only movie that opens with an epigraph from the master metaphysical poet John Donne: “I runne to death, and death meets me as fast, and all my pleasures are like yesterday.” The screen card identifies the work as “Holy Sonnet VII,” but the words actually appear to be from “Holy Sonnet I,” also known as “Thou hast made me, and shall thy work decay?” The whole thing, including the error, makes for a perfect encapsulation of producer Val Lewton: Obsessed with mortality, deeply poetic, and in a hurry.

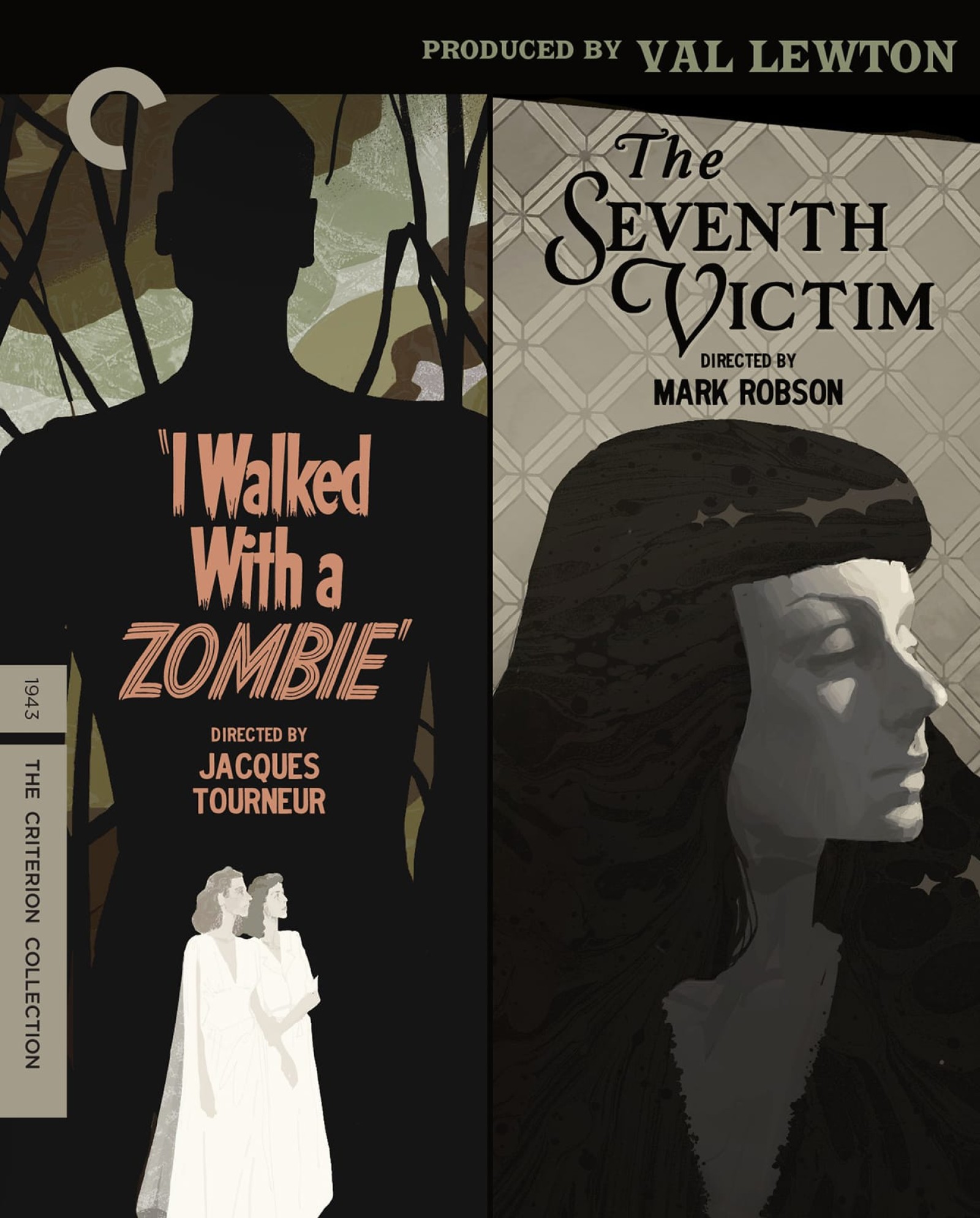

Lewton, who oversaw the RKO horror unit that churned out a series of esoteric, visually stunning, and sometimes incomprehensible horror movies in the ‘40s, gets a deluxe Criterion treatment with a new double feature set available on both Blu-ray and 4K. “I Walked With a Zombie” (1943, directed by Jacques Tourneur) and “The Seventh Victim” (also 1943, directed by Mark Robson) demonstrate a remarkable consistency of style, the handprint of a producer who exerted just as much creative control as the man for whom he once worked as a story editor/jack-of-all-trades, David O. Selznick. Tourneur may have been his go-to director and was talented enough to rise from RKO’s B ranks to direct, among others, the seminal 1947 noir “Out of the Past.” But a Lewton film was, above all, a Lewton film, and these two are among his finest.

Fed up with pricey genius–meaning, primarily, Orson Welles and “Citizen Kane”–RKO brought in Lewton to make low-budget horror movies that could compete with Universal, whose frightening franchises were fast becoming the stuff of burlesque (think 1944’s “House of Frankenstein,” with its WrestleMania-like pileup of famous monsters). The studio got what it wanted: a producer who was handed titles like “I Walked with a Zombie,” “The Leopard Man,” or “Cat People,” and made fast, cheap products. But RKO also got a committed visual sensualist who understood that what you can’t see is often more frightening than what you can and that what terrifies us are often manifestations of what lies within our hearts and minds.

Plotting is generally beside the point in Lewton pictures, which tend to run about 70 minutes and count among their mysteries character motivation and cause-and-effect. In “I Walked With a Zombie,” which, on paper, plays like a poor man’s version of “Jane Eyre,” a nurse (Frances Dee) is summoned to a West Indies sugar plantation. There she encounters a fraught family dynamic in which two half-brothers (Lewton mainstay Tom Conway and James Ellison) quarrel over a woman (Christine Gordon) who seems to have entered a catatonic trance. She is the movie’s zombie, a form of walking dead far afield from the flesh-munchers popularized by George A. Romero. The cause? It might be psychological trauma. Or it might have something to do with the inhabitants of a voodoo camp located a brisk walk from the main house.

It is typical and commendable of Lewton that the answers never quite become clear. These films unfold in a world where literal explanation wafts just out of reach and where logic and something more mystical and ineffable grapple for supremacy. Chiaroscuro lighting defines this liminal state; it’s little wonder that Tourneur would go on to leave his mark on noir, a style that thrives in the shadows. The key set piece here, in which nurse and patient take a trepidatious walk to the land of voodoo, is a masterpiece of camera movement and lighting, with images that loom over such future horrors as “Angel Heart” and “The Blair Witch Project.” But this isn’t merely a cinema of aesthetic sensation. “I Walked With a Zombie” also manages to muse on the legacy of slavery and the Middle Passage, long-lasting horrors that torment history. Postcolonial rot lies at the core of the movie, which, like so many Lewton works, ends in fatalistic tragedy.

If “Zombie” can be a little confusing, “The Seventh Victim” gets flat-out baffling. As Lucy Sante points out in her accompanying essay, “Lewton unaccountably cut three scenes that would have resolved a number of mysteries,” resulting in relationships and interactions that don’t quite add up. But the gaps might actually accentuate the eeriness. Set in a backlot in New York, focusing on a young woman (Kim Hunter, in her film debut) trying to rescue her older sister from a coven of effete Greenwich Village Satanists, it’s a movie of unabashed strangeness, clunky but laden with images that sear into the consciousness. The most potent of these is perhaps the simplest: a noose perched over a chair in the wayward sister’s dark apartment. Once again, we are running to death, Lewton’s favorite destination.

And once again, the whole is far greater than the sum of its parts, a cheap movie that punches above its pay grade. Robson, who began his career as an editor (including, Sante writes, uncredited work on “Citizen Kane” and “The Magnificent Ambersons”), lacks the panache of Tourneur, but the Lewton touch remains. We feel it in the creepily mundane boho coven (shades of “Rosemary’s Baby”), representing, as Jeremy Dauber writes of the film in his fine new book “American Scary,” “the transformation of routine spaces into sites of genuine uncanniness and mystery.” And we feel it in an atmospheric foot chase that recalls the bravura sequence of Lewton and Tourneur’s first collaboration, 1942’s “Cat People” (also part of the Criterion Collection).

A bonus documentary from 2005, “Shadows in the Dark: The Val Lewton Legacy,” features testimonies from some of the filmmakers who Lewton influenced, including Guillermo del Toro, Joe Dante, George A. Romero, and William Friedkin, who recalls how “The Exorcist” was informed by Lewton’s melding of the fantastic and the everyday. Martin Scorsese is also a fan; in his essential documentary “A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies,” he lauds the producer for presenting a personal, idiosyncratic vision within the confines of the studio system, singling out “Cat People” in particular.

Where “The Seventh Victim” opens with an excerpt from a Holy Sonnet by Donne, “Cat People” closes with one, equally somber: “But black sin hath betrayed to endless night my world, both parts, and both parts must die” (“Holy Sonnet V,” or “I Am a Little World Made Cunningly”). The man who once summed up the message of his films as “Death is good” would in fact die young, at age 46, after a pair of heart attacks in 1951.