It’s simply not enough. Especially given that as these flashbacks progress, we learn that on a visit back home to Liberia, Jacqueline was forced to flee due to conflict, taking nothing but her traumatic memories with her. The film never gives any context as to what this war or conflict is. Unless you’re historically tapped in (or motivated to Google after the film has wrapped), you wouldn’t know about Liberia’s civil war, which ended in 2003. But “Drift” does nothing to establish itself within a time period. There’s no inkling of evidence to suggest that it isn’t present day, and this oversight is glib.

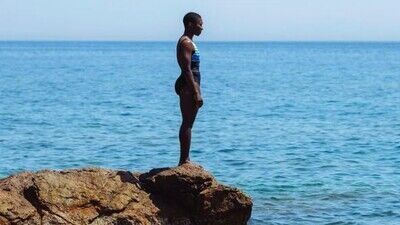

Jacqueline’s trauma is the center of the film, as is her Blackness, but no attention is meaningfully devoted to the details of either. The consequential suggestion is that there would be a lack of curiosity surrounding the context of her war-torn home, and the implication is the monolithic treatment of African countries in media as places ravaged by poverty, violence, or both, and that the depiction comes with no further questions asked. Jacqueline walks the beaches of Greece as a phantom to the privileged white vacationers and a hyper-visible figure to the city’s natives, who immediately clock her trying to sweep food at their restaurants or, as police, stop and question her.

Another African man, Ousmane (Ibrahima Ba) is a constant (at times to unbelievable degrees) popup in her days. Who is he? We don’t know, but he is always attempting to look out for her, even as Jacqueline’s hypervigilance sends her bobbing and weaving through the streets to escape him. The implied attachment is their Blackness, or more specifically Africanness, yet “Drift” treats him as a peripheral symbol or plot device depending on the scene. The true connection of the film comes in the form of Callie (Alia Shawkat), an American tour guide whose open and self-effacing demeanor inspires a relationship that cracks through Jacqueline’s defensive walls.