The two-hander is an elegant structure for a lower-budget effort: Just plop two characters together, often in a single location, and let the actors’ performances and the innate tension of the scenario play itself out. It’s a very genre-flexible conceit, malleable enough to fit everything from murderous chamber piece to yakuza thriller to pitch-black tragicomedies starring middle-aged Michiganders. In that spirit, three films I’ve seen at this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival manage to use their reduced cast and focus on pairings to intriguing effect, even if not all of them completely hold together.

“Confession,” one of three films in the fest from director Nobuhiro Yamashita, starts with a leg injury. Two men — college friends Asai (Toma Ikuta) and Jiyong (Yang Ik-june) — are making their annual pilgrimage among the snowy mountains of Japan, a kind of tradition to honor their long-lost friend Sayuri (Nao), who disappeared on one of their treks years prior. As we meet them, Jiyong’s leg has been broken, and the whirling blizzard tells them he’s not gonna make it. So he makes a presumptively dying admission of guilt: he killed Sayuri all those years ago, out of jealousy for Asai’s relationship with her. Before Asai can really process that revelation, suddenly the snow clears enough to reveal a remote cabin in which they can seek shelter. Asai drags Jiyong inside, keeping them safe from the storm… but not this unearthed secret.

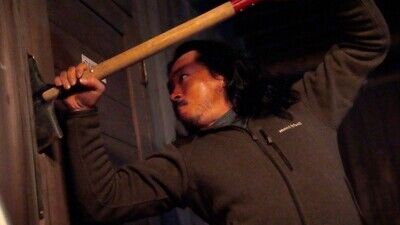

At a brisk 70 minutes, “Confession” is deliciously taut. Its early stretches build slow-burn tension as the two figure out how to reconcile this massive elephant thrown into the room. It’s Hitchcockian at first, Asai and Jiyong going through the niceties of friendship, patching up the latter’s leg, and trying to find supplies and contact the outside world. But it’s not that long before we see the lengths to which Jiyong will go to protect his crime, the two exhausted, altitude-sick friends turning to violence at the drop of a shovel. That’s where Yamashita’s direction comes alive, making elegant use of a well-established space (with food closets and cellar doors and an ominous wood-burning hearth) to find new ways to threaten and surprise Asai in his mad scramble for survival. It’s a bit Chan-wook Park in stretches, from its agonizing build of suspense to the way Yamashita’s camera keeps its grandest surprises just out of view.

Granted, it’s all in service of a story that’s a bit slight — its final act depends on a Russian nesting doll of twists that feel one or two too many to register — and the object of their animus, Nao’s Sayuri, doesn’t get much to do in flashbacks besides serve as said object. But as a slim, efficient genre exercise, its moment-by-moment mad scramble for survival, “Confession” is a fun time.

Okay, it’s maybe cheating to call Hiroshi Shuji’s yakuza thriller “Tatsumi” a two-hander, per se, but its central pair anchors what is otherwise a comparatively rote example of the genre. In a small Japanese fishing town, numerous yakuza gangs battle for control; in the middle is Tatsumi (Yuya Endo), a worn-down, cynical fisherman who disposes of bodies as a side hustle for each crime family. He’s the kind of world-weary guy who will, as we see in the opening minutes, oversee even his younger brother’s death by overdose and clean up the corpse afterward. But cracks form in his hard exterior when circumstances force him to protect Aoi (Kokoro Morita), a rebellious teenage girl, who finds herself in the mafia’s crosshairs after witnessing a power-play killing. Trapped in the middle, the two must work together to survive the various factions coming after them, and negotiate — or shoot — their way out of trouble.

“Tatsumi” is hardly a Beat Takeshi vehicle; it plays more as crime drama than shoot-em-up action, and the script lays thick its grand tragic ideas of cycles of violence and the death of humanity in the world of organized crime. It’s nothing new, but played with sufficient panache that it doesn’t get too boring — especially when Endo and Morita get to explore a brittle brother-sister dynamic as their characters become more accustomed to each other. Shoji makes efficient use of his presumably low budget, flitting between cramped gangland restaurants and sprawling car parks and fishing docks coated in an amber sheen to sell the griminess and grittiness of its setting.

It’s dour but appropriately so: it’s a movie about the emptiness of this kind of life; after all, Tatsumi casually clips fingers and pulls teeth as if he were gutting a fish. But that also holds us back from getting to know many of the supporting cast, which can sometimes confuse the complex dynamics the pair try to navigate. (That said, Tomoyuki Kuramoto stands out as the wild-eyed Ryuji, a particularly psychopathic enforcer who becomes Tatsumi’s most ardent nemesis.) Even so, Shoji paints a picture of a tense, tragic world from which there’s seemingly no escape, and the emotional toll it takes on those lost in it.

“Vulcanizadora” has already made a modest splash out of Tribeca, but the latest from Michigan-based provocateur Joel Potrykus (“Relaxer”) mines ghastly existential pathos from middle-aged malaise. A followup of sorts to his 2014 “Buzzard,” “Vulcanizadora” plops its two loser leads from that film, Marty and Derek — played by Joshua Burge and Potrykus — into the Michigan forest for some seemingly aimless wandering. Now easily in their forties, wrinkles and grey hair disrupting their metal-fan attire and whoa-man vocal tics, the pair pal around, setting off fireworks, digging up old porno mags, and talking vaguely about some kind of ritual they plan to enact once they get to where they’re going. They’re pathetic, sad, washed-up manchildren, seemingly embracing their dead-end lives and trying to wrest some control back from the years that have been lost to idleness. That is, until you figure out what they’re really trying to pull off once they get to their beachside destination, which is where “Vulcanizadora” takes on a more hilariously tragic direction.

Shot with a kind of clandestine 16mm, “Vulcanizadora”‘s look feels as ramshackle as its protagonists: pitted, pockmarked, knotted. Long takes hold on Marty and Derek trudging idly through the woods, talking themselves up to whatever they’re doing, a desperate grasp for purpose in an aimless universe. Potrykus’ smartest move, frankly, is to let its metaphorical bomb go off halfway through, and in a cruelly funny twist of fate, leaving one of the losers left to sift through the wreckage. This latter half lends “Vulcanizadora” a perverse significance, morphing into a cautionary tale of how we can become alienated even from our own desire for accountability. It’s the cruelest thing of all to feel the guilt of doing something unforgivable; it’s even worse when the world dares to forgive (and forget) you anyway.