2003. It’s an era of action movies where we’re living in a post-Matrix, post-Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon world. Those films’ major success and notoriety prompted Hollywood to try bringing Kung Fu wire work to more of their action films (Daredevil, Charlie’s Angels, The Musketeer, Bulletproof Monk). Meanwhile, two of the biggest names in the genre – Jackie Chan and Jet Li – were attempting to expand their brand into the American market — with films that many of their fans considered to be watered-down versions of their previous works. Around the same time, Doug Liman debuted a newer visceral style of action in his film, The Bourne Identity, which would make its own mark on action films to come. However, somewhat hidden in all that activity was a budding star in Thailand who had taken his amazing physical skills and called back to some of the classic, acrobatic action that defined Hong Kong’s most beloved period of martial arts movies. That star was Phanom Yeerum, but he would soon adopt the stage name Tony Jaa, and his movie Ong Bak would give action films the kick in the pants that it needed.

Allow me to backtrack to where I said Ong Bak threw back to the kind of action that defined Hong Kong cinema. A lot of the action in Ong Bak strongly resembles the kind of daredevil stunts and hardcore fighting that Sammo Hung and Jackie Chan would become famous for. However, in the late 70s and early 80s, Thai action cinema had their own champion in Panna Rittikrai. Although Jaa and Ong Bak would only take influence from classic Hong Kong movies, Panna had actually been doing similar action when he broke out around that same era. He had started his own stunt team while he was in college and in 1978, they would show off their skills in a movie Panna directed and starred in called Born to Fight. And in Born to Fight, you can see the seeds being planted for what would eventually be the kind of style that Tony Jaa’s movies would adopt – like the slow motion take which emphasizes full contact made by the fighters or the instant replay of a dangerous stunt so the audience can soak it in and rewatch in amazement. It’s hard to say if it was influence or perhaps it was the general style of action movies at the time, but Panna’s gritty display of fight scenes implemented similar tactics that were incorporated in Sammo and Jackie’s movies. However, the more limited reach of Thailand’s cinema would keep Panna and his team in shadow for a while. Add to that, Sammo and Jackie had the benefit of their Peking Opera training to give them a more showy display of their action, thus giving them an entertaining edge with their weapons play and the acrobatic ability to sensationalize movements. Having said that, Panna could go toe-to-toe with their brutality and insane stunt commitment.

Panna would eventually take a young Tony Jaa under his wing as one of his stuntmen and occasional actor. Jaa was a huge asset on the stunt team as his athleticism and skills made him a stand out talent. This would actually lead Jaa into breaking out in Hollywood early on with an uncredited role as Robin Shou’s stuntman in the 1997 film Mortal Kombat: Annihilation. There are even some moments of foreshadowing his signature dynamic moves. In Ong Bak, while Jaa would take the spotlight as the lead star, Panna still played an integral part in shaping the action scenes.

The plot of the film is a simple, but an effective one. It’s very fairytale-like in nature. The title Ong Bak refers to the sacred Buddha statue that resides in a small, humble Thai village. The people of the village have thrived for years on the crops and good fortune that the statue has brought upon them. Then, one day, a visitor from the city steals the head of the statue in order to sell it. The residents are devastated and the crops begin to die out, so a young villager, who has been proficiently trained in Muay Thai, volunteers for the task of traveling into Bangkok and getting the head of the statue back. This young warrior is Ting, who is played by Jaa. Ting was an orphaned child who was found and raised by a monk who has the guilt of once killing a man using his Muay Thai. Ting, himself, has become quite the fighting specimen and is on the journey to also becoming a monk since he’s been uncorrupted by outside forces. Although now, he must face a trial by fire with this mission.

Ting ventures into Bangkok and the audience is almost immediately hit with all the evils of the city. There’s illegal street racing, gambling, prostitution, drug use, gangs who have affinity for American movies like Serpico…and…um, Spy Game? Once Ting arrives, he runs into George, a hapless conman who gets by from running scams all over the city. He also happens to be an outcast from Tings village. However, he denies the connection when Ting tries to latch onto him for any semblance of an ally. George is played by Phetthai Vongkumlao (pʰét.tʰāːj wōŋ.kʰām.lǎw). And I do apologize if I mispronounce any of these Thai names. George is the comic relief of the film. He tries and mostly fails to run scams with his partner Muay, played here by Pumwaree Yodkamol (Phum-wari Yotkamon). Again, I apologize. George attempts to evade Ting, but in an effort to make money in an underground fight club, Ting unknowingly becomes a cash cow. He is also well equipped to protect George from any reprisals from his cons, so when George realizes he can use Ting, he agrees to return the favor by helping him look for those responsible for taking the Ong Bak head. And that’s your basic plot right there — Thief steals thing, Jaa fights to get it back. What else do you need?

The movie is unapologetically a thinly veiled showcase for Jaa’s skills. While there are vanity projects that can get quite egregious when it’s obviously plagued with narcissism, Jaa takes a cue from stars like Jackie Chan and Jet Li by not playing the badass, but a simple, peaceful man who only fights when he has to. This makes it easier for us to cheer for him. Ong Bak happily flaunts not only his fighting prowess, but his physicality for parkour-type action in a time that barely predates Parkour. The movie kicks off with a cool capture the flag sequence on a grand tree in the village. Here, we get a glimpse of Ting’s athleticism as his climbs and navigates through the complicated pattern of branches all while trying to evade and fight off challengers trying to take the flag. We are shown right off the bat that the stuntmen will take some hard falls for the sake of the action. It’s a crazy madcap sequence and there’s actually a similar scene in one of Jackie Chan’s earlier movies called Dragon Lord where hordes of fighters try to get to a golden egg on top of a bamboo pyramid.

Jaa would aim to carry on the tradition of Jackie’s style of interacting with his environment in a foot chase scene that was specially designed to show off his similar abilities. Ting helps out George when some guys try to rough him up, when they show up with more guys, the chase is on and George and Ting try to weave their way through the busy streets of Bangkok. There are many obstacles in Tings way including food markets with some dishes being cooked, a bevy of items being loaded onto trucks, and cars making their way through the streets. In the making of Ong Bak, you can see how the obstacles were designed around Jaa’s ability to flow through with various acrobatic techniques.

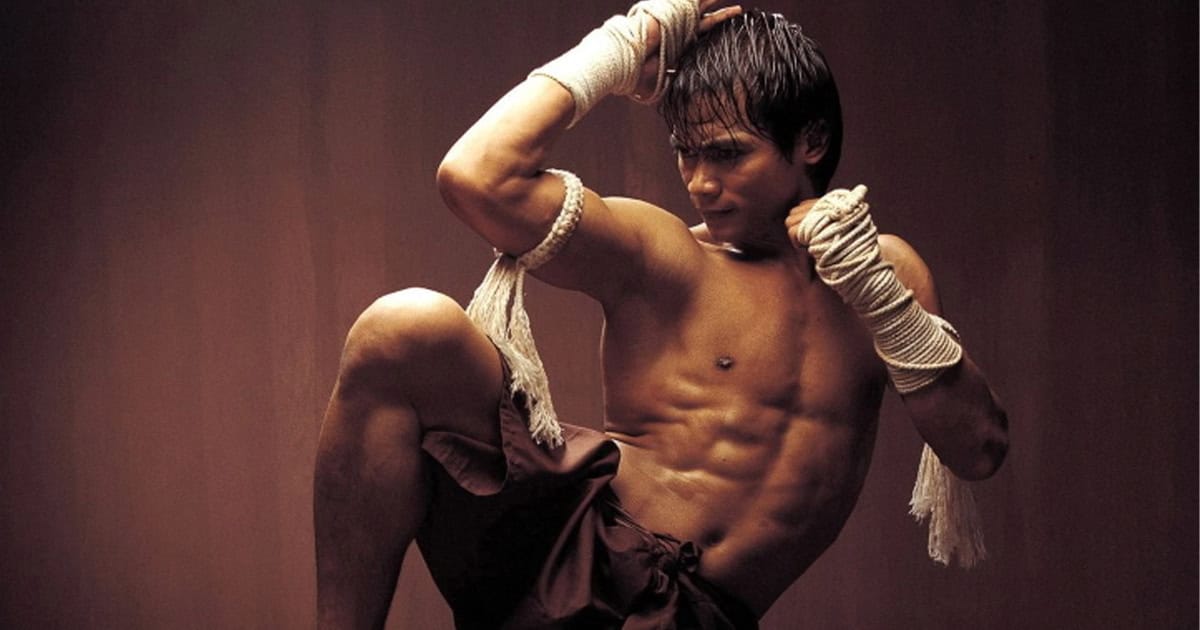

The movie isn’t just a coming out party for its star. Ong Bak also proudly aimed to showcase to the world some of the more authentic practices of Muay Thai. In Van Damme’s 1989 movie, Kickboxer, a lot of attention was paid toward the art. While there are traditions shown, the action itself was more or less of what can be found in his other movies. In an early scene in Ong Bak, there’s a nice introduction to the style when Ting performs a kata using a list of offensive and defensive moves. He shouts the name of the moves as he performs, which makes this scene a “Muay Thai 101” for viewers. You can see the major emphasis the style places on elbows and knees for maximum damage. What makes this part even more impactful is that later in the movie, he uses all these distinctive moves during some of the fight sequences.

The fight design doesn’t have too many complicated hand-to-hand choreography like a lot of Hong Kong martial arts films. The combat scenes are an interesting mix of grit and spectacular moves. This includes Jaa displaying his amazing jumping ability to soar across the room for big hits or pulling off some really showy kicks. In between all that, the choreography can get surprisingly grounded. There are times where the hits hold a lot more weight since they aren’t film graceful and they don’t instantly put down the opponent. The sound design even holds back on typical bombastic movie sound effects for some realistic impact sounds. The final fight between Ting and another Muay Thai fighter particularly has some impressive moments of realistic exchanges that emulate the spontaneity and chaos of a real fight in a way that doesn’t seem choreographed.

One interesting aspect to note is sometimes in these fights, Ting looks seemingly invincible as he takes multiple hits but keeps coming. Some may call this out as him being too unrealistically invulnerable. However, the mentality of Muay Thai displayed here is one that’s rarely depicted in films, where fighters are conditioned to be “hardened.” They will not emphasize defense. They’ll just eat punches and kicks in favor of looking “harder” than the opponent. To those not familiar, it may seem like a cop out that our hero is just unfazed and it makes him look less of an underdog, but this is more of an element that’s somewhat lost in translation.

Ong Bak made Jaa a star in his native Thailand. He, Panna and the film’s director, Prachya Pinkaew, wanted this movie to bring Muay Thai into the mainstream around the world. So, they would insert little easter egg messages into the film to shoutout to international directors. There’s a scene in the movie that features a chase through the streets with compact Thai vehicles called Tuk Tuks. And it’s like the filmmakers are making it their own special Thai version of a Blues Brothers chase with these Tuk Tuks. During this sequence, there’s a shot that features a message to French director Luc Besson that reads, “Hi, Luc Besson. We are waiting for you.” And in the footchase scene mentioned earlier, there’s a shot where some writing on the background shouts out to Steven Spielberg and reads, “Hi, Speilberg. Let’s do it together.” Not only is the message hilariously translated, but they spell Spielberg’s name incorrectly. While Spielberg didn’t respond, Luc Besson, who dabbles in martial arts action here and there, even collaborating with Jet Li on a few occasions, would become the one to help distribute this movie internationally as the “Besson cut” became available everywhere. His version added new music and trimmed some scenes. The company Magnolia would distribute his version in America in 2005, and they would send Jaa around the country in a press tour to introduce himself to U.S. audiences. Even performing a demonstration during halftime at a Dallas Mavericks game.

While I can’t say specifically if Ong Bak was thee major influence, but after the release of the film worldwide, shortly, the popularity of Parkour and Muay Thai would skyrocket. Besson would even produce a French action movie called that seemed to emulate Jaa’s style while it featured French martial artist, Cyril Raffaelli and Parkour founder, David Belle. It’s hard not to make the distinction, Tony Jaa does make both practices look awesome, so it would be easy to see his movie as being a big contributor to both movements. Ong Bak made it seem like he could do anything. It’s surprising they didn’t let him rap in the movie.

Jaa would reunite with the dream team of Panna and Prachya for the next movie, Tom Yum Goong, or The Protector. The success of their first movie got them a much bigger budget for this sophomore effort. Where Ong Bak had Jaa going to the city to get back his statue head, The Protector had him traveling to Australia to get back his stolen elephant. Yup, his stolen elephant. In that film, he constantly shouts, “Where’s my elephant?” Which is a pain that only Bart Simpson can relate to. The Protector would follow similar story cues, even having Phetthaireturn as another comic relief character. But the action is turned up with more elaborate and jaw dropping sequences. There’s even a bit where Jaa bumps into Jackie Chan. However, Chan is played by a lookalike.

There would be two sequels made to Ong Bak that were filmed somewhat back-to-back in 2008. Here, Jaa also took a seat in the director’s chair. Those films would be sequels in name only as Jaa played a completely different character in an unrelated story that took place in the year 1431. The reception of both Ong Bak 2 and 3 would not be as warm as the first film (Ong Bak 2 was one of the first movies JoBlo ever covered at TIFF).

Jaa would eventually break into several Chinese and Hollywood productions. These include American films like the Vin Diesel movies, Furious 7 and xXx: The Return of Xander Cage. He could also recently be seen in The Expendables 4. And on the Chinese side, he would also co-star in the sequels to SPL aka Kill Zone and the Ip Man spinoff, Master Z.

Ong Bak looks crudely made by modern standards. It doesn’t have a lot of flash, but it doesn’t need to. It has an ace up its sleeve with Jaa. The confidence the film has in its star and its native traditions makes this film an entertaining watch, even if it gets silly at times. It’s simple. It’s raw. It’s hard-hitting. Much like the style of Muay Thai itself.