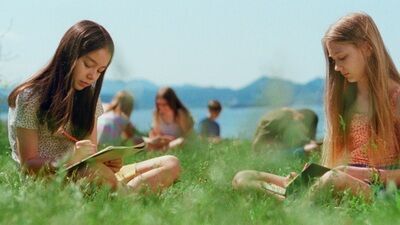

That exercise that cracks Steve takes place at a couples retreat that he’s attending with his wife Judith (Ally Maki) and daughters Stephanie (Nyha Huang Breitkreuz) and Emmy (Remy Marthaller). Judith has recently lost her mother, and the grief has sent her marriage into something of a tailspin. They both seem to be actively engaged with trying to mend broken bridges, but there are early signs that this venture was Judith’s idea, and Steve is attending reluctantly. Meanwhile, the teenage Stephanie makes friends with girls of a similar age while the younger Emmy seems more prone to fear, fascinated by the story that a nearby cave can allow communication with the other side. Maybe she can see grandma again.

Don’t worry — “Seagrass” isn’t a traditional ghost story, and yet it also kind of is on an emotional level. It’s about the specters of decisions we make as adults regarding family and partners. It’s about that feeling that we wish we knew more about the ones we can no longer learn about — Judith regrets every time new friends Pat (Chris Pang) and Carol ask questions about her mom that she can’t answer. Grief isn’t just about loss, it’s about regret over every conversation we never had with people who are gone.

As Judith and Steve push through counseling that seems to be pulling them further apart, they start to emotionally fracture in a way that threatens their entire family. Pat and Carol become a dangerous comparison in that they represent a false ideal — the “If they can do it, then so can we” mentality that often poisons actual growth. Hama-Brown’s film keenly understands the human capacity to compare grief and struggle, often minimizing and simplifying both in ways that can become tragic.

That sense of imminent tragedy makes a lot of “Seagrass” play out like a slow-burn thriller, one of those timeless stories of adults who get so caught up in their own nonsense that their children suffer, often quite literally. The foreboding is so resonant that even a scene wherein Emmy slowly moves across a pool to a purple ball that she’s been eying feels somehow both joyous and slightly terrifying at the same time — kind of like childhood.