What is the best Australian movie ever made? Walkabout? Wake in Fright? The Piano? Picnic at Hanging Rock? The Babadook? All worthy contenders, no doubt, but they’re all wrong answers. The only acceptable response regarding the best movie from the Land Down Under is Mad Max, George Miller’s marauding motorist mania that celebrated its 45th anniversary in 2024. Never mind the billion-dollar franchise it spawned, the creative ingenuity and low-budget DIY filmmaking of the original remains one of the most impressive cinematic feats on record.

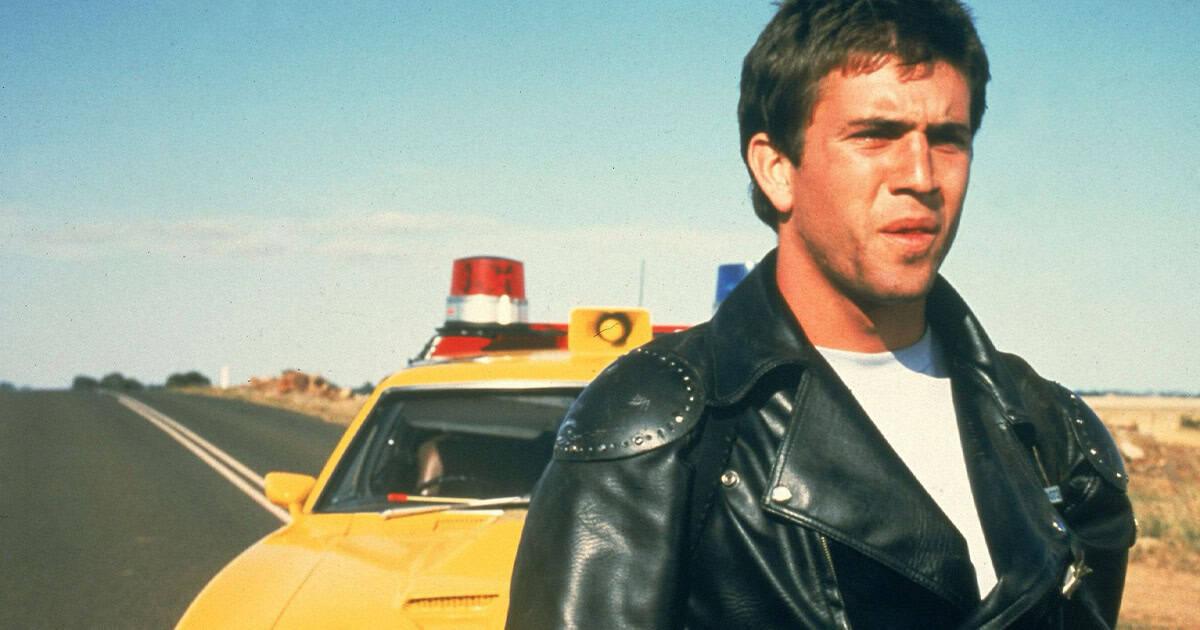

A true independent movie with a rebellious spirit, Mad Max was made in just 12 weeks for a paltry $350,000 yet went on to gross $185 million worldwide. The film introduced the world to Mel Gibson, who would go on to play the badass road-racing Main Force Patrol officer Max Rockatansky twice more en route to becoming a bona fide Hollywood action star. Now, with the law-enforcing legacy (that includes our picks for two of the best action movies of all time) continuing with Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga this week, it’s only right to peer through the rear-view mirror and find out What Happened to the trailblazing O.G. After all, some of the crazy production details and insane behind-the-scenes stories defy belief. Of course “They say people don’t believe in heroes anymore. Well damn them! You and me, Max, we’re gonna give them back their heroes!”

Mad Max was developed as George Miller’s feature-length film debut in the early ‘70s following Miller’s time working as an Emergency Room doctor in Sydney. Miller grew up in rural Queensland and witnessed three of his close friends die in violent motorcycle collisions and often witnessed the types of fatally gruesome injuries seen in Mad Max in the ER. In 1971, Miller enrolled in film school and met fellow filmmaker Byron Kennedy, who would go on to share screenwriting credit with Miller for Mad Max. The duo made a short film titled Violence in Cinema Part 1, a semi-blueprint for Mad Max. Miller also hired newspaper editor James McCausland to flesh out the script after realizing the best Hollywood screenwriters, such as Ben Hecht and Herman Mankiewicz, had journalistic backgrounds.

Despite being his first feature-length film, Miller had a clear vision to make a visceral, hyperkinetic “silent movie with sound,” relying on classic filmmaking techniques introduced by such pioneers as Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. With zero screenplay experience, Miller focused on the action scenes and overall structure. Meanwhile, McCausland concentrated on the dialog and subtext, using the 1973 Australian oil crisis as inspiration for the post-apocalyptic setting. Miller also found inspiration in the 1975 post-apocalyptic road movie A Boy and His Dog. However, in 2015, Miller admitted that the dystopian atmosphere was not part of the original screenplay and was born out of necessity. Due to the small budget, Miller could not afford many extras and well-maintained buildings. Instead, Miller opted for a desolate wasteland to place the story. As such, the opening title card was added to signify the story occurs after a world war.

Miller and McCausland presented a 40-page treatment to the Australian government, which funded most of the film. Miller and McCausland also raised money by performing medical house calls, with the former treating patients and the latter driving. The filmmakers ultimately raised $350,000 to $400,000 to make Mad Max, which equals roughly $1.6 million when adjusted for inflation in 2024.

When the casting process approached, Miller considered an American to play Max Rockatansky to broaden the movie’s appeal. After venturing to Hollywood to recruit, Miller backtracked realizing that a big-name American actor would be too costly. By design, Miller hired unknown actors to play roles in the film so viewers wouldn’t be distracted by stars from previous projects. Miller’s first choice to play Mad Max was Irish actor James Healey, who turned down the script due to its sparse dialog.

Once Healey declined, casting director Mitch Matthews recruited several new grad students from Australia’s National Institute of Dramatic Art, searching for “spunky young guys” to play various roles. American-born actor Mel Gibson wowed Miller and Matthews during his audition and was cast as Max Rockatansky while still a drama student. Gibson was paid $10,000 for his performance. Meanwhile, Gibson’s friend and school roommate Steve Bisley was cast as Max’s police partner, Jim Goose. Bisley also encouraged Gibson to audition for the film. The main biker villains Nightrider (Vince Gil), Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne), and Fifi (Roger Ward) all appeared in the 1974 biker gang movie Stone, which also inspired Miller. Of course, Keays-Byrne, who patterned his performance in the original after Genghis Khan, went on to play Immortan Joe in Mad Max: Fury Road 36 years later.

Due to the limited resources and time allotted, many background biker extras In Mad Max were members of real-life outlaw motorcycle gangs in Australia that were paid in beer for their services. Several members of Toecutter’s gang were real members of The Vigilantes, a motorcycle club in Melbourne. The movie exudes a lawless sense of anarchy because of the genuine guerilla filmmaking tactics and practical moviemaking methods demonstrated throughout the production.

Charged with $400,000 budget tops, principal photography on Mad Max began in November 1977 and wrapped by December. The film was originally planned for a 10-week shoot, with six weeks dedicated to first-unit photography and four weeks on second-unit stuntwork and car chases. Unfortunately, four days into filming, original actress Rose Bailey was injured in a bike accident. Bailey, who was set to play Max’s wife Jessie Rockatansky, was replaced by Joanne Samuel after a two-week production delay. All told, first-unit filming on Mad Max took six weeks in 1977, while second-unit photography was completed over another six weeks in 1978. The majority of the film was shot in and around Melbourne in Victoria. Miller chose to film Mad Max in a widescreen anamorphic format, attempting to use lenses discarded by Sam Peckinpah for his 1972 film The Getaway. Only one of the lenses worked; a 35mm lens Miller and Director of Photography David Eggby used to film Mad Max. For one scene, Eggby held a camera while riding as a passenger on a motorcycle going 110 miles per hour. The death-defying filmmaking methods perfectly embody the spirit of the movie. Early on, road signs reading Anarchy and Bedlam can be seen, two apt descriptors not fabricated for the film. The roads genuinely exist.

A handmade labor of love in every sense, Mad Max reflects the manic antiauthoritarian energy of the production techniques themselves. Described by Miller as true “Guerilla Filmmaking,” shots were flat-out stolen by mounting cameras to the top of cars, closing roads without legal permits, and capturing footage in areas forbidden by the authorities. For example, the first scene filmed involved Tim Burns, who plays Johnny the Boy, busting the chain on the overpass phone. If you look closely, Burns appears rushed because he was. Miller lacked legal permission to film the scene and raced to capture the footage before authorities arrived. As for Burns, he remained in character during the production, annoying his cast mates to no end.

Miller and his crew avoided using walkie-talkies to remain undetected by Police scanners and often cleared road wreckages by themselves after filming crash scenes. Ironically, Miller’s attempts to avoid the authorities while making Mad Max backfired when the local police became interested in the production and assisted the filmmakers by escorting vehicles and shutting down roads to accommodate filming. The police cars in the film are not props; they are real decommissioned police vehicles that were more affordable than the alternative.

As a first-time filmmaker with a restricted budget, Miller faced several problems early on. It got so bad that Miller felt he couldn’t complete the film and quit the project. Producer and co-writer Byron Kennedy phoned fellow Aussie filmmaker Brian Trenchard-Smith and asked if he would take over directorial duties. Trenchard-Smith declined and advised Kennedy and Miller to hire a talented first assistant director instead. Miller pressed on, and completed the film, with Ian Goddard replacing Alex Rappel as the First AD. Goddard also doubled as the safety coordinator for Mad Max. Despite being a low-budget first-time film, Goddard and his four assistants were so organized in their radio communications that no road accidents occurred while filming.

Although no road accidents occurred during filming, several controlled crashes did. A local Kawasaki dealer donated 14 Kz1000 demo motorcycle models for production, only three of which were returned in complete condition. The others were deliberately crashed for the adrenaline-fuelled action scenes. By the end of filming, 14 vehicles were purposely destroyed for the crash and chase sequences. Some claim Miller’s blue Mazda Bongo van was crushed in the opening chase scene, but it was only used for the establishing shot before another was replaced for the crash.

When filming the blue van crash scene, the engine was removed from the vehicle before off-screen assistants pushed into traffic. The engineless van weighed so little that it spun out of control on impact and accentuated the explosive spectacle. Milk buckets were placed atop the van’s roof to add to the chaos.

Nightrider’s infamous death crash was filmed using a military-grade booster rocket installed in the back of his tricked-out 1972 Holden Monaro. The car was meant to crash into the fuel tanker but sped out of control, veered away, and missed its mark. The car flew off the road into a field and continued for a quarter-mile. The graphic explosion of Nightrider’s crash was filmed separately using a towed car under safer conditions.

One of Mad Max’s most memorable scenes involves Jim Goose giving the three-wheeled cyclist a “get out of jail free card.” This was a sly in-joke among Miller and his cast and crew. The real-life biker gang members used as extras were forced to drive themselves to the set because the budget couldn’t accommodate travel. As a precaution, Miller gave each biker written letters to present to police officers to get them out of trouble if they were pulled over. Due to their authentic appearances, the real-life bikers were often discriminated against and treated poorly in town.

Speaking of Goose, his fiery death was considered too graphic in New Zealand, and the film was banned in the country. The death was also similar to a real-life incident involving a biker gang in New Zealand shortly before the film came out. Following the success of The Road Warrior, Mad Max was eventually exhibited in New Zealand in 1983.

As for other real-life injuries, actress Sheila Florence, who plays Max’s friend May, also suffered a mishap. While running with the antique shotgun, Florence fell and broke her kneecap. Her hip and leg were placed in a plaster cast and Florence returned and completed her scenes.

For gearheads especially, it’s hard to discuss Mad Max without mentioning the killer cars seen onscreen. Max drives two vehicles in the film, a yellow “Interceptor” and a black “Pursuit Special.” The Interceptor was a tuned-up 1974 Ford Falcon XB that cost $3,500 to build, 3.5 times Gibson’s salary, and 1/10th of the overall budget. The Interceptor was also a former Victoria police car. Meanwhile, the Pursuit Special was a 1973 Ford XB Falcon GT351, a limited-edition hardtop model discontinued in 1976. The badass road burners are among the most iconic movie cars ever constructed and helped popularize Mad Max when it skidded into theaters.

The small budget and lack of resources for Mad Max also led to several cost-cutting measures that give the film a tactile, homemade quality. For instance, no stunt doubles were used during the fistfights; the actors performed the combat alone. Meanwhile, Mary’s home is an abandoned farmhouse that had to be furnished by the filmmakers with their personally owned items. Only Mel Gibson wears genuine leather clothing, everyone else appearing in leather wears much cheaper vinyl outfits. Looking closely, you can see several characters’ pants split horizontally at the kneecap due to the cheap material. For instance, when Max fights Johnny his left knee is torn. When he gets shot later, his right knee is ripped. When Max handcuffs Johnny in the movie, plastic toy cuffs are utilized despite Max saying they’re made out of “high-tensile steel.” The fact that Mad Max was filmed in 12 weeks with such limited resources only makes the ingenuity of Miller and his crew more impressive.

Part of the impressiveness derives from the patient post-production process. Once principal photography wrapped, Miller and Kennedy edited the film during a 4-month process in their friend’s apartment in North Melbourne. More stunning yet, they cut the film on a homemade editing machine that Kennedy’s father engineered for them to use. Editor Tony Patterson spent four months cutting the film until he had to leave for another film. Miller then worked closely with editor Cliff Hayes for three more months to finish the process. Despite Hayes and Patterson receiving official editorial credit, the final cut of Mad Max was edited by Miller and Kennedy. According to Miller, Kennedy would edit the sound in the living room while Miller would cut the images in the kitchen. Even through the post-production phase, Mad Max was stitched together by hand, giving the movie an undeniable organic quality that remains timeless.

Another unforgettable part of Mad Max is the Gothic musical score arranged by Australian composer Brian May. Not to be confused with the Queen guitarist of the same name, Brian May was instructed by Miller to create an ominous, Bernard Herrmann-style score reminiscent of classic Hitchcock movies. Miller became a fan of May after hearing the score for the 1978 sci-fi film Patrick. According to May, he and Miller spent substantial time working on the music despite having little money.

Of course, the grand irony of Mad Max – if not the historical legacy – is that it set a Guinness Book of World Record for the most profitable film in 1979. The film cost roughly $400,000 to produce and grossed over $100 million worldwide, becoming the most financially successful independent movie ever made. Mad Max held the record until The Blair Witch Project broke it in 1999. For 20 years, Mad Max reigned supreme as the king of independent movie success. The film put Australia on the map as a cinematic power player. It also launched the illustrious career of George Miller, whose legacy continues to be defined by Mad Max and its highly entertaining sequels.

Speaking of, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga blazes into theaters on May 24, 2024, continuing the lasting legacy Miller began 45 years ago. Following Furiosa, Miller plans to make Mad Max: Wasteland with Tom Hardy, which could develop as a TV show. Until then, it’s time to sign off and say, that’s What Happened to Mad Max!