Wonka ends up toiling in a basement laundry processing facility along with other indentured servants, including Abacus Crunch (Jim Carter), a onetime accountant to Slugworth, and Noodle, who quickly bonds with Wonka, creating a sibling-like dynamic that’s one of the freshest, most appealing aspects of the movie. Wonka’s wish to liberate his buddies purifies his desire to succeed in the chocolate business: he’s not just doing it for himself and his mum, he’s doing it for them, too. But it’s a rocky road to victory. The script is relentless in its willingness to force Wonka to take two steps back for each step forward (something Chalamet actually does in a scene where he’s walking down the steps—you don’t often see a metaphor conveyed by an actor’s footwork).

Even the most elaborate plans unravel due to unforeseen circumstances or the villains’ influence, requiring on-the-spot improvisation, which fortunately is something Wonka and Noodle are good at. And when all else fails, this is a fantasy—sometimes a cartoonish one. We’re never entirely clear on how many resources the down-and-out Wonka actually has at his disposal, and what we do see makes us wonder if he’s an otherworldly creature whose only limitations are conditioning or psychology. The chocolate-making “travel kit” that he carries is practically a tiny factory that seems to have its own power source. When he finally does get to open his own chocolate shop (come on, now, like you thought he wouldn’t get to do it?) it’s up and running overnight, without a worry as to where to get the money, the materials, the permits, and the army of contractors required to make it happen. It’s all quite cheeky, though, like the transition in “The Blues Brothers” where Cab Calloway is told that he needs to stall for time at the theater where the big show is supposed to occur, and there’s a cut to a curtain going up to reveal Calloway and the band in on a 1930s Art Deco set wearing white tuxedos and launching into “Minnie the Moocher.”

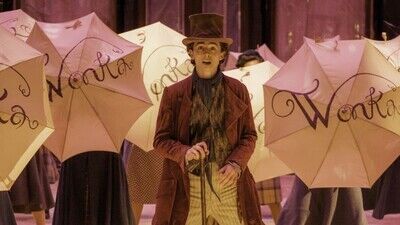

“Wonka” is not only unapologetic in its contrivances, manipulations, and absurdist embellishments, it lets its goodhearted trickster hero and a few other characters comment upon them—not as blatantly as a Bugs Bunny or Deadpool might, but practically. Nathan Crowley’s production design, Lindy Hemming’s costumes, and Chung-hoo Chung’s cinematography create a universe that has a certain grittiness and is connected to reality through economic distress, but is otherwise the audiovisual equivalent of one of Wonka’s candies. There’s a class system here, and the one percent rules over everyone else. But there’s no racism. “Wonka” avoids complaints that Wonka’s future factory workers, the Oompa-Loompas, are imperialistic caricatures of nonwhite people by casting Hugh Grant as the lone example, a chocolate thief who visits Wonka when he’s asleep, and making him sort of an English leprechaun obsessed with his own version of the fabled pot-o’-gold. Dahl’s tendency to equate conventional beauty with virtue and ugliness with nonstandard body types is also mostly AWOL here, save for the the running gag of having the bribe-taking police chief get bigger the more candy he consumes.