From the start of his fame, Costner has made no apologies about his earnest, everyman demeanor. Sure, he had swagger in “Bull Durham,” but in films like “The Untouchables,” “Field of Dreams” and “JFK,” he played men who were slightly square. They weren’t cool, but they weren’t trying to be—they were duty-bound to do something greater than themselves. His characters are often mocked or misunderstood, but others’ opinions don’t matter to Costner’s men—they’re on a mission, and they approach it with an unwavering zeal.

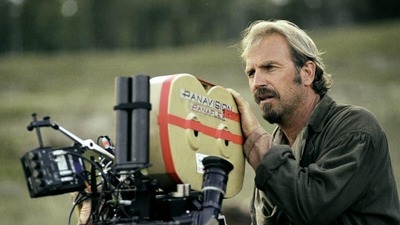

Does that make them heroic or corny? Timeless or hopelessly out-of-touch? What has made Costner such a fascinating figure is how he embodies those tensions, leaving viewers to fight amongst themselves over what his image means. I’ve never interviewed Costner, never crossed paths with him, so I have no idea how much his real self overlaps with his onscreen persona. I’m only judging the work. But when he turned his attention to directing in the late 1980s, his stardom on the rise, he helmed movies that streamlined his essence into their base elements. Those films have not always been good, but as I await “Horizon,” I think they’re his most representative. They allow him to let his cornball-flag fly.

“Dances With Wolves,” “The Postman” and “Open Range” are all Westerns. In them, he rides a horse, looks out at the horizon, pondering the grandeur of the natural world. He is looking for something ineffable, or maybe he’s trying to escape the life he once led. The orchestral score swells in the background—he may seem like an ordinary man, but he will be called upon to do extraordinary things. He will meet the moment—after all, it’s what any honorable person would do in the same situation.

The best of his three directorial efforts remains “Dances With Wolves,” which won seven Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. It is perhaps now best-remembered as the film that beat out “Goodfellas,” with many complaining at the time (and now) what a travesty that was. Based on the novel by Michael Blake, who wrote the screenplay, “Dances With Wolves” is not as great as that Martin Scorsese classic, but it remains a completely respectable, frequently affecting drama about a Union soldier, John J. Dunbar, who wants to die at the start of the film and ends up being reborn on the vanishing frontier, befriending the Sioux people and falling in love with a white woman (Mary McDonnell) who was adopted by the tribe when she was just a baby. John is a good man tired of war, and he finds in the Sioux a kinder, more thoughtful community than the one from which he came. As he is given a Sioux name, Dances With Wolves, he becomes the person for whom he’d always been searching inside himself.