The early films of innovative documentarian Errol Morris — “Gates of Heaven,” about pet cemeteries, “The Thin Red Line,” a staggering true-crime store — waxed profound on matters of mortality and morality while maintaining a wry sense of humor. His more recent works have been ambiguous—his 2018 “American Dharma,” a portrait of political ogre Steve Bannon, irritated a lot of viewers here at the Biennale for not coming down hard enough on Bannon. Maybe not coming down on Bannon at all. I saw the strategy as a kind of turnabout—Morris knows his audience is made up largely of people with progressive politics and showing Bannon as an intelligent, cagey, canny and at times ingratiating figure was a way to showing that audience why the figure once nicknamed “Sloppy Steve” by the other ogre who used him most constructively was a person worth taking seriously.

In any event, maybe the times are such that Morris finds wry humor besides the point. As Nick Lowe sang in “Cracking Up,” “I don’t think it’s funny no more,” and there was certainly nothing funny about the Trump administration’s policy of separating illegal migrant children from their parents. This is the subject of Morris’ new “Separated,” the movie with which I kicked off my screenings at the Venice Film Festival, aka the Biennale. Morris’ film is a solid, infuriating piece of work. There are laughs to be had, but they’re of an extremely mordant variety: in limning portraits of Trump apparatchiks like Scott Lloyd and Kirstjen Nielsen, he shows a bureaucracy delighting in their toughness at executing a “tough” policy but then blanches and ultimately backs down when public reaction paints them as, you know, sadists. Well, the fish does rot from the head down, and this kind of nonsense is par for the course from Trump, who gets affronted when he thinks people are treating him “nasty.” This movie practically advertises itself as an alarm bell for the potential second administration.

I’ve never cottoned much to the work of Chilean director Pablo Larrain; as I stated in my review of “Neruda” almost ten years ago, his work tends to be “laudable in its ambitions and ultimately unsatisfying in its execution.” And that’s when I was trying to be nice. After “Neruda,” I avoided seeing his subsequent pictures, which means that “Maria,” his treatment of the opera singer Maria Callas, which I was asked to check out for this journal, is the only portion of Larrain’s ostensible trilogy on Famous Women Of The Latter 20th Century, or whatever he calls it (the others were “Spencer,” about Diana, and “Jackie,” about Bouvier Kennedy Onassis) that I’ve actually seen.

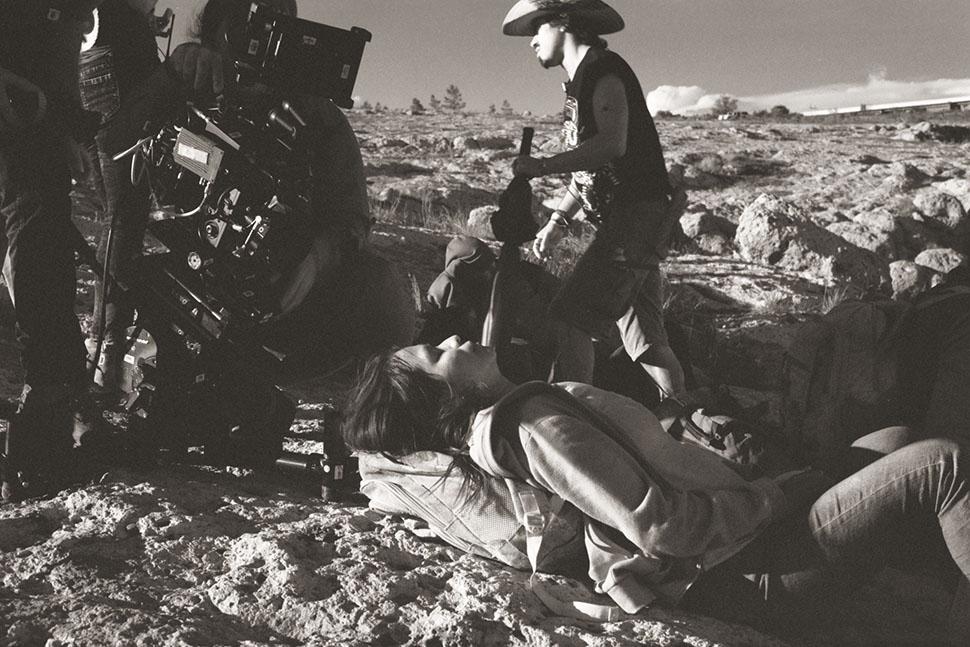

I did not care for it. Treating the singer’s whole life via a flashback-seasoned account of the last week of her life, it is not only stiffly self-important, it also has his standard skirting-magic-realism touches. While in “Neruda” his title poet had a perhaps-imaginary antagonist, here the ailing and neurotic Maria Callas (portrayed by Angelina Jolie with a haughty pretension that matches that of the director) has an imaginary amanuensis called Mandrax, named, yes, after the sedative she abuses and that a subsequent generation may remember as the Quaalude. “Mandrax? Don’t mind if I do,” read my impatient notes. Soon after, I began musing whether the film’s backers were under its influence—this is one leadenly paced movie. Larrain’s dialogue is lazily on the nose throughout; late in the movie, Jolie’s Callas meets President Kennedy, and he asks about her relationship to magnate Aristotle Onassis. “He’s your whatever,” he says wryly. As someone who was alive in 1962 or so, I can assure readers that nobody used the phrase “Whatever” in that way back then. Sure, I was three in 1962, but I still had ears. The film ultimately has nothing meaningful to impart about the art form to which Callas devoted her talents and life, or much of anything else for that matter.

“Kill the Jockey,” a frequently amusing and even more frequently deliberately confounding Argentinian comedy from Luis Ortega, isn’t much on messaging either, but it’s colorful and lively. It’s a tale of transformation and maybe redemption, but not in terribly conventional terms. Its original title is just “El Jockey” and its portrait of the title character is well-nigh unforgettable. As Remo, Naheul Perez Biscayart gets to make the most of his sad eyes and the near-Keatonesque (as in Buster) set of his sad-sack jaw. His horse racer is a relentlessly self-defeating sort (pretty much the first time we see him astride a horse, he’s bolted from it in a jaw-dropping manner) despite his colleague and rival Abril (Ursula Corbero, widely seen in stateside fare such as “Girl’s Night Out” and “Money Heist”) being a person worth sticking around for. This enrages certain racing interests, who want him, if not dead, then severely constrained. It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense in real-world terms (my hope that this would be a derby thriller in the mode of Kubrick’s “The Killing” was abandoned about five minutes in), but it’s a lively entertainment if you can trot with its absurdism.

Kevin MacDonald’s documentary “One to One: John & Yoko” frequently feels like several films at once. A tense archival chronicle of American in turmoil over the Vietnam war and the possible criminality of then-President Richard Nixon, a portrait of post-flower-power Greenwich Village, and an account of two prodigious and prolific artists trying to foster change and keep from being kicked out of their adopted home.

MacDonald makes a point of underscoring the fact that when John Lennon and Yoko Ono moved from Great Britain to NYC, they traded a multi-acre secluded estate for a small loft in downtown Manhattan and tried to make a life among the people Lennon was for a period interested in social agitation for. Lennon here comes across as often arrogant (his messianic streak preceded his solo career; check out “The Word” on the Beatles’ Rubber Soul) and starry eyed all at once, but the movie ultimately shows how he could worry over an idea until the point when he ultimately saw, and did, the right thing. In this case, it’s how he transformed a grandiose program of protest into a single concert raising money for children abused at a New York mental institution. It’s interesting that this period coincided with the creation of what was Lennon and Ono’s worst album together, Some Time In NYC, which demonstrated with extreme prejudice that neither John nor Yoko had any knack whatsoever for the Protest Song. The movie is compelling because they are compelling, and because the time really was a fraught and frightening one. We could use a guy like John, warts and all, nowadays, to be sure. I think Errol Morris might agree.