One teacher (James Le Gros) even calls out the value of surprise in his own work. “There’s spontaneity in that pot. It’s its own thing,” he says, as he passes a vase around a circle of students. The sentiment applies to all of the art in the film: the way Lizzy intends for her sculptures to turn out from the kiln is different from how they actually end up, especially in the case of the burned sculpture. And the way that Lizzy’s work is received is also different from the way that Lizzy expects her work to be received. Success, in her eyes, is the sculpture not breaking when it cools; her smaller sculptures coming out of the kiln looking exactly as she’d planned doesn’t do anything to alleviate her stress about the show coming together. The scorched sculpture was intended to be the focal point of Lizzy’s show. In the scorching, it becomes the focal point on which the movie turns, too.

What matters is the work, but the work isn’t the only thing that matters. Art is, by alternating definitions, both useless and essential. It isn’t necessary for the base layers on Maslow’s hierarchy. But if it were entirely useless we wouldn’t spend so much time making it, and thinking about it, and so on. It’s important; it isn’t the only thing. But it adds color and texture and life to the world, just as the world adds color and texture and life to it.

At the art show, the camera gets a good long look at Lizzy’s ceramics on their plinth, then studies her father’s face as he makes his circle around the room, drinking everything in. This is the turning-out moment, the unclenching from Lizzy’s extreme inward focus as she tries to complete the art for her show on time. Lizzy makes the work for herself, because she has to. She never explains that motivation, because the film takes her need to create something completely for granted. It doesn’t need a reason to exist. It’s made worthwhile in the making, and it’s made worthwhile by the delight it brings to the people who see it. Lizzy’s father—a retired ceramicist himself—is pleased by the work he sees. “You were daring with the colors!” he remarks. She’s surprised him with her art.

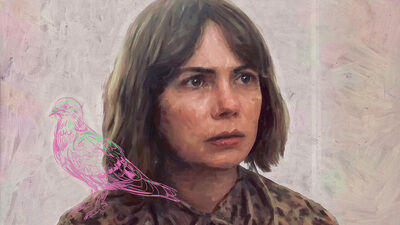

Lizzy’s fighting the burden of expectation throughout the film. She expects the world to be a certain way; she expects the hot water to work and her day off to be artistically productive, and she expects her glazes to come out of the fire at just the right shade. The hot water doesn’t get fixed. (When Jo, preparing for a show of her own, complains that there might not be a catalog to go with the exhibit, Lizzy snipes back: “Things usually get done, just not on time.”) Family emergencies keep cropping up. Lizzy and Jo take joint care of an injured pigeon, another distraction to add to Lizzy’s pile of grievances, another thing to take her away from her work. The pigeon had always been there—the film’s soundtrack includes the bird burbling just outside Lizzy’s studio right from the beginning. She resents it at first, then slowly takes on a feeling of ownership about the bird’s care, telling Jo how best to change the newspapers out of its box. Late one night in the studio, as she eats chips and dissociates, Lizzy reaches over to lightly scritch the bird on its head. Sometimes we make peace with our distractions. Sometimes they add unsearched-for texture to the movements of our imaginations.